Indian Jewelry Brands – Advance of the Transformers

February 05, 13

“Brands,” says Abhishek Gupta, president of Gitanjali Gems, “are the transformation force in Indian jewelry retail.” This is true as, by the very nature of the way they do business, brands differ radically from traditional Indian jewelry retailers. Brands thrive in organized retail formats. Currently, organized jewelry retailers account for between just 8- and 10 percent of the market in India. But the number of players in organized retail is growing. Branded jewelry is also growing, at the rate of some 2 percent every year. “Organized retailers will enjoy compound growth,” predicts Gupta.

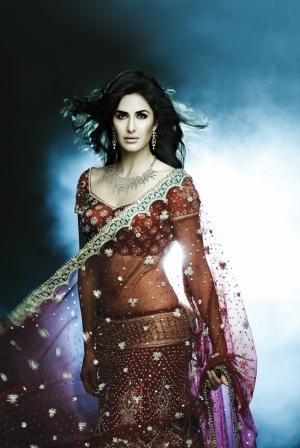

Image: Gitanjali |

Gitanjali is one of the pioneers of jewelry branding in India and runs a slew of brands that include several international names such as Stefan Hafner, Porrati and the former De Beers brands, Nakshatra, Asmi and Sangini. The firm operates 1,100 retail points and another 3,000 through other entities.

Talking about the future of the Indian industry, Gupta cites the example of the garment sector. “A few decades ago, most people in India had their clothes tailored. All that has changed and today, most people buy their clothes readymade.” He explains that among the chief reasons for this shift is the fact that consumers actively want the enhanced retail experience that organized players provide. “They have also begun to appreciate the value of wearing a brand,” he says. Another explanation is that Indians have become increasingly time-conscious. “The Indian consumer has become impatient and is now not ready to invest a lot of time and effort in the acquisition process,” which is why brands, with their enhanced retail experience are filling the gap for time-poor buyers.

Gupta does, however, that Indian jewelry brands are not structurally the same as brands in the rest of the world. “In any other country, a piece of branded jewelry that cost $1,000 would have material and component costs of around $150, with the value of the brand constituting the remainder of the price tag.” He points out that in India, brands compete with unbranded jewelry, which is sold more as a commodity assessed for its investment value. “Indian branded jewelry has to have high intrinsic value too if it is to compete successfully in the marketplace.”

Gupta says Gitanjali stretches the concept of the brand around high intrinsic value product. “We offer an enhanced buying experience and a number of other value drivers including intangibles. The consumer is thus willing to pay a premium above commodity prices for our branded jewelry.”

Sandeep Kulhalli, vice president, Retail & Marketing for India’s largest jewelry brand, Tanishq, says his brand’s strategy is to provide alternative value drivers while simultaneously offering the consumer the high intrinsic value that he or she wants. Tanishq does not come from any ancient gem and jewelry pedigree. It is owned by the globe-spanning Tata industrial group, which also owns the British premium car brand Jaguar-Land Rover. Still, Tanishq respects and operates to the pulls and pushes of the market drivers for traditional Indian sales. “We have been trying to build up our brand to create a market for the socially-driven purchase of jewelry. The add-on is that it also provides all of the investment value that the Indian consumer typically seeks,” he says.

Image: Talwarsons |

Kulhalli however, bemoans the way Indian jewelry is typically retailed. “In no other product category does the customer know the value of the material that goes into it. But in India, this is almost essential in jewelry. The market has been ruined. We’ve managed to change that to some extent, but most consumers still don’t value design. Intrinsic value is all they want.”

He goes on to note that this is why retailers usually spout words like “wastage” (the amount of material lost from a piece of gold during the fabrication process) and “making charges” (the cost of production). Typically, both of these have to be low. “This means that very low value is attached to the karigar’s [skilled jewelry artisan’s] artistry. We want to even change their working conditions and how they work.”

Kulhalli does not think there is much difference in terms of the product when comparing branded jewelry in India and elsewhere. The main difference he says is the design aspect, which is a premium outside of India. He thinks that Indian-origin design will grow more popular with time as the country becomes economically stronger and more significant. “But,” he says, “India needs to make its jewelry more affordable. In the U.S. they spend on average between $300- and $400 for a piece. So we need to match all those price points and most importantly, we need to fit into that system. Our designs can be an attraction if we can put them together with the required quality and price points.”

Looking to potential export markets is not, however, a priority for Tanishq, which closed two U.S. outlets during the 2008 economic slowdown. “We haven’t looked at reopening them or launching any new ones because currently, we have enough and more to do here. It doesn’t look like we want to hurry back in the near future.”

Kulhalli also mourns the fact that Indian jewelry retail has been very slow in transforming itself. It hasn’t yet understood the importance of consumer assurance. “The purity of the gold used in jewelry is the biggest question for consumers and the jewelry retail industry has not done much to reassure them.”

According to Kulhalli, much of this has to do with Indian jewelry retail’s origins. “Most traditional jewelers started out as karigars. All they had were their skills. They were given some gold and told to turn it into a piece of jewelry. The client was asked to write off the amount of gold that was lost in the fabrication process – the ‘wastage’ and a little of the gold could be kept by him as his fee. By altering the purity of the gold in the jewelry, he got to keep more for himself and thus increase his fee.”

Kulhalli says this process has gone on for literally thousands of years and has also influenced the way jewelry is viewed in India. The focus on material value is due to the way the industry evolved.”

Tanishq, with its industrial background, is trying to counter this age-old system with its gold-purity issues. “We put an electronic karat-meter in all of our stores and upended the system.” By being able to accurately assess the gold in any piece of jewelry, Tanishq is also able to offer buy-backs at proper valuations for any jewelry the consumer brings into the store. Traditional jewelers will usually only accept pieces they themselves have fabricated.

Image: Gitanjali |

“We use technology to achieve this,” Kulhalli says. “The old jewelry is melted in front of the customer and purified. The pure gold retrieved from it is weighed again in front of the consumer. They love this because in today’s world of soaring gold prices, they get better products at old gold prices.”

Even though it caters to the Indian consumer’s need for high intrinsic value, Tanishq places significant value on its design inputs and quality assurance. “Since everything is open and transparent, customers are willing to pay a premium. This is why we are the brand of choice.” The assurance also allows Tanishq to cater to a countrywide clientele. Traditional jewelers are limited to narrow geographic areas.

Ravinath Mohandas of VNM Jewel Crafts of Ernakulam points out that Indian’s do not yet value brands and the artistic inputs that go into jewelry. “In a perverse sort of way,” he says, “hallmarking – which is obviously a consumer-assurance initiative – has killed design initiative in the country. Consumers are now interested in the intrinsic value of the piece. Also the development of Indian brands was stunted by the imposition of excise duty. Now that excise duty has gone we are starting anew.”

The excise duty Mohandas is referring to is a tax that is imposed on all branded products in India. The government had brought jewelry under its purview. This resulted in inspectors deeming the proprietary marks jewelers have traditionally imprinted on their jewelry to be brand marks, thus making the jewelry taxable. After a unified industry representation on the matter, the tax on jewelry was withdrawn.

Mohandas also makes the point that even if product brands do not exist, there is no shortage of store brands in Indian jewelry retail. “There was once a brand called Tanishq but now every retailer is a store brand,” he observes. So you have to see a store as a brand too. And when viewed this way, Indians are buying brands. Retailers are not afraid to call themselves brands.”

Mohandas thinks that collective industry promotions will enhance the appreciation of these brands and brands in general, along with brand values will take off. “This is only as long as our own people don’t spoil the brand idea by playing fast and loose! The potential for branding is immense.” He adds that branding will help jewelry retain a value greater than its intrinsic assessment.

He cites the example of the technology giant Apple. “People are willing to pay higher prices than the competition just because they value the brand. There are premiums on the latest products. Branded jewelry has the potential to get into that space. But now, with the investment motive dominating everything, we can’t get the premium that a new design deserves.” Branding, he adds, will have benefits for even existing jewelry. “Like Apple, we too could have a good aftermarket for old jewelry.”

Branding therefore holds the potential to radically transform the Indian jewelry retail industry. The transformers are coming.