The Rise and Steady Descent of Diamond Production

July 03, 14

However, the modern history of diamonds, the one that gave birth to the winning slogan, started in 1870 when the first diamond mine started working in South Africa, just three years after the first diamond was found in that country.

In the less than 150 years that have passed, diamonds have mainly been mined in South Africa, then Southern Africa as mining expanded into Namibia (1908) and Zimbabwe (1913), slowly shifting to Congo and West Africa in the 1930s, where for the first time “leading” was a split term for leading by weight (Congo) and value (West Africa).

In the 1950s, production and total value of mined diamonds start to rise but it was not until the 1980s, as diamond production dominance shifted to Botswana and Russia (by value and volume, respectively) that these figures start to shoot up.

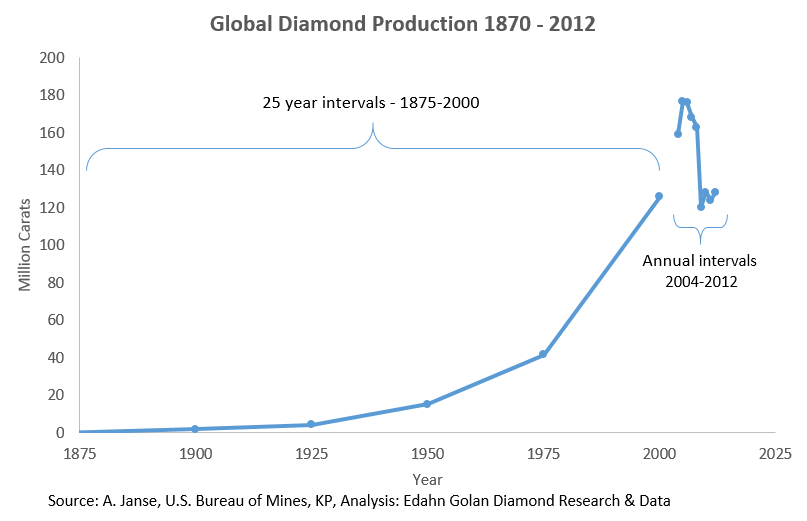

Summer calls for some light reading, so apologies for the figures. By 1900, 30 years after commercial diamond mining started, global diamond production was estimated to total 1.9 million carats, according to mineral data compiled at the time by the U.S. government. In the next 25 years, production more than doubled to 4.2 million carats in 1925.

From there, the increase is staggering. Another 25 years pass, and global diamond production more than triples to 15.2 million carats in 1950 and production rises to 41.6 million carats by 1975, completing a 10-fold expansion in 50 years.

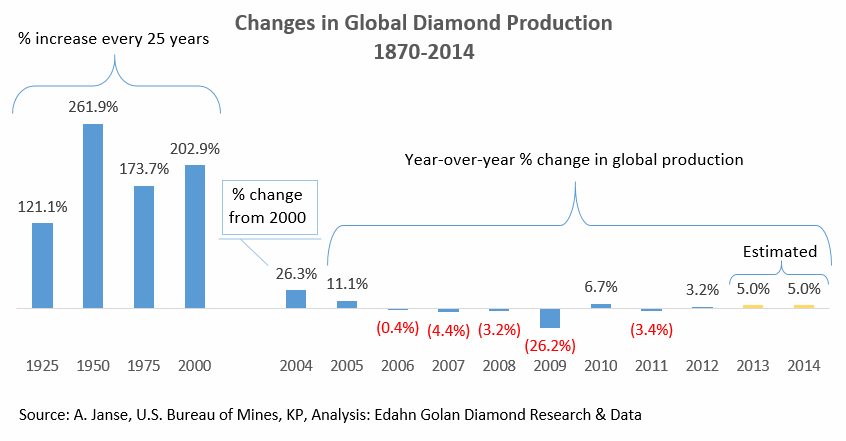

In the next 25 years to 2000, global diamond production keeps rising to reach 126 million carats, tripling again. Is this a lasting trend? If the past 14 years are a good indicator (and they are), the answer is ‘No’, although the potential was there. In 2005, production increased again to 176.7 million carats according to Kimberley Process figures, up more than 40 percent in five years, but then, it all dropped.

After years of running full steam upwards, production is falling. Contrary to the impression the above graph gives, this is something that happened before, in response to either a major global political catastrophe or a macro-economic disaster: after the First World War broke out in 1914, again in the 1930s coinciding with the Great Depression, in the early 1940s during World War II and in the 70s along with the global fuel crisis. What the above graph does reflect accurately is that the long-term trend was continued growth. The recent large drop in production seems no different, happening in conjunction with the 2008 economic bust. In fact, the large decline coincided with a plateau in production.

Figures for 2013 are not out yet, and 2014 is only half way through, however both Alrosa and De Beers, the two largest producers by volume, reported increased production in 2013 (7 percent and 12 percent respectively) and during the first quarter of 2014 (6 percent and 18 percent).

Considering these figures, and that the two are responsible for nearly half of the world’s production by volume (48.7 percent in 2012), let’s estimate a conservative 5 percent increase in global production for each year (production by the two and Rio Tinto was 58.9 percent of the global production in 2012, has increased collectively by 11.5 percent in 2013). That means that growth in production in the 14 years since 2000 was just 12 percent, nothing near the three-digit increase seen in each of the quarter centuries since diamonds were first commercially mined. That is a serious change in the global production trend.

If you read my previous Memo column, the one that discusses Alrosa’s huge untapped resources of nearly 900,000 carats (‘No Major New Mines’ Answers the Wrong Question, June 19, 2014), it may seem contradictory to the above. It’s not. That column discussed the potential while this column the realization.

The ballistic trajectory that started nearly a century and a half ago has passed the apex and headed down, but the drop will not be as dramatic as the rise or end in a wild bang, even though the overall trend would be a slow tapering off. That is where the Alrosa resources – and other resources – come into play. A steady supply with some ups and downs and even some sharp declines should only be limited to major macro political and economic disasters, followed by the inevitable recoveries.

Follow Edahn on Twitter

Get in touch on LinkedIn

Connect on Facebook

Or visit EdahnGolan.com