Economics 101: A Course on Added Value

January 29, 15

The president of the International Diamond Manufacturers Association (IDMA), Maxim Shkadov, is clearly in pain. Recognizing that the supply of polished diamonds is far exceeding demand, he lashed out in a “dear colleague” letter widely distributed this week against the rough producers whom, he says, “consciously turn a blind eye to developments in the downstream section of the pipeline.”

Continues Shkadov, “Their sales and pricing models do not incorporate or take into account the demand and the prices paid for polished, nor do they assess the cost of manufacturing, let alone the financing needed to turn rough into polished goods.” He then quotes De Beers’ president and CEO Philippe Mellier as saying “…that’s not down to me.”

Argues Shkadov in his letter, “As IDMA president, it is my mission to defend the interests of those players in the diamond supply pipeline who are most vulnerable to the policies of the producers.” Of course, one can only wish him much success in doing that, but this doesn’t mean that he should discredit those whose views are not the same as his, or put professional reputations in a questionable light. If I may borrow from his words, it is DIB’s mission to protect our own integrity. Let me quote further from Shkadov’s letter.

Analysts Present ‘Pure Fiction’…

States Shkadov, “The figures that industry analysts have presented at recent industry gatherings are also pure fiction. Last June, during the 36th World Diamond Congress in Antwerp, Martin Rapaport said that the cost difference between rough diamonds and the wholesale cost of diamonds is 30 percent. In December, at the inaugural World Diamond Conference in India, Chaim Even-Zohar raised that figure to 35 percent. (Why he did so is beyond me since in his annually published pipeline, it usually stands at 16-18 percent.) My colleagues and I – the manufacturers in this world – are telling you: it is zero percent!”

After noting Philippe Mellier’s “complete lack of understanding of what it takes to manufacture diamonds,” Shkadov continues, “so, dear colleagues, let’s tell the truth, to each other and to those who are willing to listen. There is no profitable income to be made in diamond manufacturing. There is certainly not a 30 percent to 35 percent margin, nor is there added value generated at a rate of 16-18 percent. There is only a gain of 5-6 percent but that is not added value or profit – and this percentage does not cover financing, expenses and modest staff salaries,” laments Shkadov.

Shkadov Confuses Added Value with Profit Margins

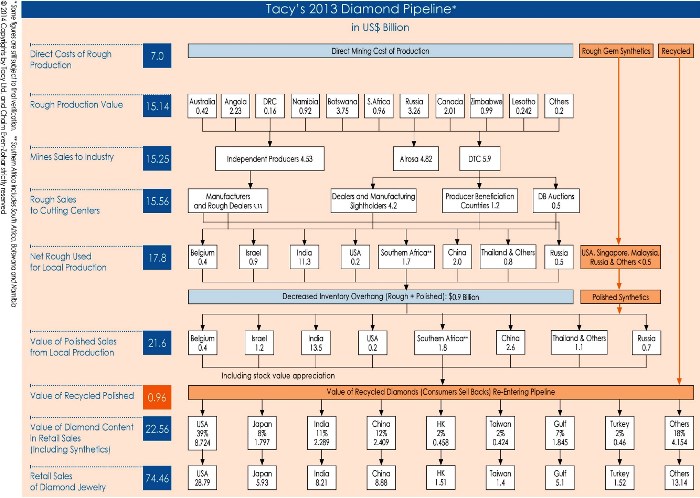

In economic models, the difference between the sale price and the production cost of a product is the value added. We consider the industry added value as the difference between the cost of rough and the costs of the resultant polished. At the New Delhi conference that Shkadov referred to, I showed our figures on presentation screens – for everyone to see and to photograph. The 2013 diamond pipeline shows that some $15.5 billion worth of rough was sold to industry and that some $21.6 billion worth of polished was sold as polished (in polished wholesale prices) further downstream.

The pipeline also shows that these sales include some $0.9 billion withdrawal from inventory. Thus, the added value is about 29 percent – the same (30 percent) range as other analysts are citing – but certainly not 35 percent! None of my figures suggest that. At the New Delhi conference, I also showed our forecasts for 2014, which is the year Shkadov describes in his diatribe. From those preliminary figures, we can see an added value of slightly below 29 percent.

It’s the Margins that Count

In any situation, profits are just one component of the added value. The bulk of added value is the labor cost, the depreciation costs, operational costs, financing costs, interest costs, etc. In our profit models, which my colleague Pranay Narvekar and I presented in New Delhi, we said that when we look at the entire diamond industry as if it were one company that made purchases of rough diamonds worth $16.6 billion (in 2014) and had polished sales of $22.5 billion, the net operating profits would come to zero. I actually showed this slide during the banking panel, and quite a few people were upset: how can one tell bankers that the industry doesn’t make money?

I clarified that this was a “total picture” – there are companies that make money – some companies actually make a lot of money – while there are others that clearly lose money. That doesn’t necessarily make them banking risks; that all depends on a company’s equity and the quality of the collateral. During my presentation, I also showed that in 2014, we saw a $1 billion withdrawal from inventories, which was slightly more than in 2013. That may have been expedited in recent months: when prices are sliding down, and debts have to be returned to banks, many players will sell off inventories at a loss – only to prevent a greater loss later on.

In business, we refer to the gross or net profits as the margins. We actually separate out the stock profits from the operational profits. According to our research, in the difficult 2009 year, the downstream industry (the manufacturing and trading sector which we view as “one company” which acquires and processes rough and sells polished) still made a meagre $0.2 billion, but took a hit of $1.6 billion loss because of reduced inventory values. In 2011, however, on an operational level industry lost $0.3 billion, but it made some $2.5 on the inventories it was holding.

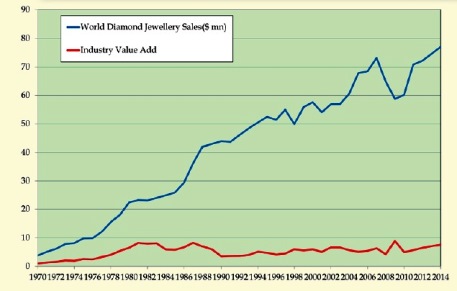

Pipeline Comparison: While the Industry Topline has Grown, Value Addition has Stagnated

In our presentation in New Delhi, we showed the bankers (and the audience) that in 2010, on polished sales of $18.9 billion, the industry as a whole made $2.4 billion profits. In 2011, on sales of $22.6 billion, the industry made $2.2 billion, followed by a loss in 2012, in which the industry’s global profit and loss accounts showed a $0.4 billion loss on $20.7 billion sales. In 2013, in fact, the industry had a better year: $1.6 billion profit on $21.6 billion sales. These are all the total profits/losses which are skewed by stock gains/losses. For 2014, we estimated that profits are zero, but we have yet to finalize the losses on stocks. As an industry, we find that the profit made in 2013 came to 1.9 percent of sales, following one year of loss and preceding what currently seems like a zero rate for 2014.

Who is the Fiction Writer Here?

Shakov’s sentence: “There is certainly not a 30 percent to 35 percent margin, nor is there added value generated at a rate of 16-18 percent. There is only a gain of 5-6 percent but that is not added value or profit – and this percentage does not cover financing, expenses and modest staff salaries,” doesn’t make any sense to us – neither content-wise, nor figure-wise.

Maybe Shkadov is looking through a very limited and wholly unrepresentative Russian perspective. The value addition on larger stones (which are the stones Russia cuts) is 15-16 percent as mentioned. I am not sure whether Shkadov realizes that there are hundreds of millions of small stones cut and polished in India, where the labor cost (a part of the added value) exceeds the cost of rough. Thus, there, the value addition is well over 100 percent. Nevertheless, there too, margins can be minimal or negative. These are two entirely different matters.

Is it all an exact science? No. When looking at the pipeline, it gives a “snapshot” of what takes place at each level of the value chain. There are a lot of diamonds out there. It takes an average of some 2.5 years for a diamond sold by the producer to reach the finger of the consumer. The retail sector generally has a product turnover of once a year. If polished sales (at PWP) in 2014 reached $22.5 billion, this means that the entire pipeline would be holding well in excess of $55 billion diamonds (including rough translated into polished prices).

Our traditional supply and demand models are constantly revised and refined. Our 2013 pipeline – published once more for reference – includes synthetics and recycled diamonds, factors that have become too major to be ignored. If, in 2013, we estimated these additions still to be in the $0.5 billion range, their impact in 2014 was considerably larger. If Shkadov analyzed the precise areas (especially sizes and colors) of polished price softening, he might even recognize that there are other factors impacting supply, value added and margins.

Comparison to Car Dealers…

In JCK’s Rob Bates’ excellent and very revealing interview with Philippe Mellier, the latter made the (probably quite unfortunate) comparison between diamantaires and car dealers. “If you look at a business I know very well – car dealers – they make 1.5 percent, and they are all smiling and happy about it,” Mellier was quoted as saying.

In Shkadov’s letter, he refers to Mellier’s comparison and explains: “Well, maybe it is time Mr. Mellier – and others – take a moment to learn this business and the diamond manufacturing world. Unlike the car industry, the diamond industry is completely different because very different polished diamonds are produced from diamonds that start out as very similar pieces of rough – sold at similar prices.

“One rough stone will result in a Renault Laguna (a top luxury sedan model) but the other just a Renault Clio (a lower end, much cheaper compact). While we are blessed with highly advanced planning, decision making and manufacturing technologies, the outcome of production is never guaranteed – and as we, members of IDMA, all know, this means that we not only cannot predict the added value of our production, we can also not guarantee or plan its quality and character,” notes Shkadov.

His argument would have been stronger had he mentioned that car dealers do not sell on credit, that car dealers do not take the risks that diamond dealers take, including price risk, credit risk etc. and, most significantly, when they buy a car, they know exactly which model they are getting. They do not need to make commitment months before finding out what they are receiving. Diamantaires are more like car assemblers, who are at the mercy of their suppliers.

Just Cheap Rhetoric

However, we really don’t want to comment on anything written by Shkadov beyond his unwarranted attacks on “analysts.” Says Shkadov: “If the margins are as indicated by the analysts, why on earth would Sightholders and other core clients be ready to sell off their boxes – wrapped and sealed – for a margin of just 1.5 to 2 percent? As if they are car dealers who sell a car out of the showroom?”

The bitter truth is – as this analyst also stated in New Delhi but Shkadov clearly wasn’t listening – taking the downstream industry as a whole, there were no profits in 2014. With falling prices, the industry cannot assess yet how much really was lost. Rough trading is still one of the ways to make some money: making as little as a 1.5-2 percent immediate cash profit on a box is often a more interesting commercial proposition than cutting and polishing these goods.

If Maxim Shkadov only understood the difference between value added and profit margins, he would not have written his letter. Attacking those who make a living by analyzing the industry’s economic performance and sharing their findings with larger audiences – as we are doing – is not the right way to start out a new year. It is precisely for those who may have missed the Economics 101 course on Economic Added Value that we do the work that we are doing.

To read Maxim Shkadov's letter, click here